In our new format we are going to write about books we are currently reading. This is an experiment and a work-in-progress. So please don’t expect a polished review or an in-depth reading with final conclusions and what not. What we want to do in this category is to give ourselves a format that allows us to experiment with different texts and approaches – and sometimes even read books in conjunction with others to see whether these constellations might lead us somewhere… Hope you’ll enjoy it – please let us know what you think!

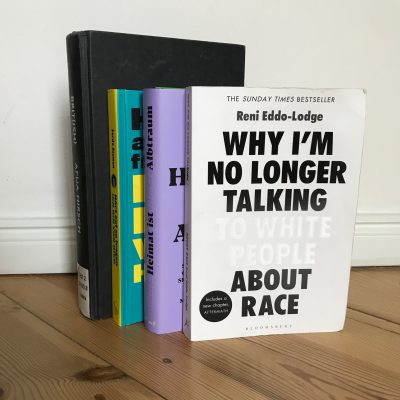

Today’s “Caution – Reading in Progress” post will be about the following four books:

- Reni Eddo-Lodge: Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. (Bloomsbury, 2017)

- Afua Hirsch: Brit(ish). (Jonathan Cape, 2017)

- Fatma Aydemir, Hengameh Yaghoobifarah (eds.): Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum. (ullstein, 2019)

- Ferda Ataman: Ich bin von hier. Hört auf zu fragen! (S. Fischer, 2019)

This idea started with Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and Afua Hirsch’s book Brit(ish) and my wish to write something about it that makes people want to read it and go on their own journey of privilege checking and maybe finding ways to engage (or set up) anti-racist activities. But at the same time, I was scared I wouldn’t do these authors and their texts justice if I were to write a ‘normal’ review. So instead, I want to write some of the points that touched me most and how these two books resonate with two other books that were recently published in Germany.

Read it, Reflect Upon it and then Make a Difference

All four books listed above share their authors’ experience of not just feeling different from the white society they live or grew up in, but of being made to feel different by racist structures and cultures that they call out and try to dismantle. And they share that their author’s families or communities are often portrayed as a problem, in particular (but not only) in these times where populist parties are on the rise and their vocabulary is taken over by mainstream media. All four books contribute to replacing the “single narrative” that describes Black British, Afro-German or Turkish German people as problem with multiple narratives and perspectives.

While I was reading Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and Brit(ish), I needed to take several breaks to let their words sink in and recover from what I had read. Both books are incredibly dense and multi-layered, and both authors share many stories about the racism they have faced. Both books put their individual experience in a wider and historical context, both relate to those who have fought racist structures before them, and both also look into questions about class and race and “racialised class prejudice” (R. Eddo-Lodge).

While I was reading Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and Brit(ish), I needed to take several breaks to let their words sink in and recover from what I had read. Both books are incredibly dense and multi-layered, and both authors share many stories about the racism they have faced. Both books put their individual experience in a wider and historical context, both relate to those who have fought racist structures before them, and both also look into questions about class and race and “racialised class prejudice” (R. Eddo-Lodge).

Afua Hirsch uses a much more personal approach and explains how she has tried to come to terms with her identity, body and family history in a structurally racist context, while Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book felt more like a wake-up call or being shaken to finally do something about our racist societies from within; but both books are remarkably personal while at the same time describing something that goes wrong on a bigger level. And how racism can also serve as a means to maintain the capitalist order:

“[…] immigration blamers encourage you to point to your neighbour and convince yourself that they are the problem, rather than question where wealth is concentrated in this country, and exactly why resources are so scarce.”

(R. Eddo-Lodge, 206-207).

Entangled Histories

Both books have many things in common and the authors share some views, but they have different takes for example on “Black History Month”. While Reni Eddo-Lodge praises its contribution to a fuller picture of the British history including Black people – “I had been denied a context, an ability to understand myself.” (9) – Afua Hirsch problematises that it might encourage people to think that there is ‘national history’ on one side, and the ‘other’, i.e. Black history, on the other side. I understand both reactions and I really do see the problematic aspect of singling out Black British history. Nevertheless, I think it’s unfortunately still necessary to draw some ‘extra’ attention to our entangled histories and Reni Eddo-Lodge comments that it took quite some effort to dig it out. It would be great, though, if this was just one step on the way to an understanding of Black history as a part of the history of the places we live in. As both writers point out on several occasions, our histories are not least entangled because the Northern, i.e. white nations exploited African, Asian and other countries for centuries. The famous “We are here because you were there”. And Afua Hirsch comments: “Reassessing British History is not about race, it’s about integrity […] Seeing things differently would affect reality for everyone.” (A. Hirsch, 86)

“Get Angry. Anger is useful.”

Reni Eddo-Lodge and Afua Hirsch explain which behaviour has hurt them, e.g. people who claim they ‘don’t see colour’ and make Afua Hirsch feel like they’re “erasing [her] very identity while claiming to be doing [her] a favour” (A. Hirsch) or white feminists who are not aware of their own privilege and blatantly reject to engage in the fight again racism (R. Eddo-Lodge). Both authors continue to talk about their feelings at the risk of being hurt even more – and both are very aware of that.

It must be really exhausting – and many Black British authors have quoted Toni Morrison on racism as a distraction in the past (see quote below) – to explain to readers like me what the problem is.

“The function, the very serious function of racism, is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language, so you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly, so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Someone says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of that is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

(Toni Morrison)

I am thankful to the authors of the books I’m currently reading that they’re still talking to us about racism nevertheless, but I understand that it shouldn’t be people of colour educating us. The information is available, and we must care to look for it. I understand that nobody needs my tears or “white guilt”, as Reni Eddo-Lodge puts it. I want to follow her suggestion: “Instead, get angry. Anger is useful. Use it for good.” (221)

There’s no Word like ‘Heimat’

After reading Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and half-way through Brit(ish), I discovered the German collection Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum, edited by Fatma Aydemir and Hengameh Yaghoobifarah, published by ullstein (part of the Bonnier group).

After reading Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race and half-way through Brit(ish), I discovered the German collection Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum, edited by Fatma Aydemir and Hengameh Yaghoobifarah, published by ullstein (part of the Bonnier group).

Heimat is one of these almost untranslatable German words that means more than just “home” or region of origin. This word has been instrumentalised by individuals, parties, and not least past and present fascists to exclude those they wanted to exclude, e.g. Jewish people, Black people, Muslims, etc. On top of it all, the German ‘Home Office’ was renamed to carry the addition “Heimatministerium”, with no other than a populist Bavarian minister at its top, as the editors explain in the foreword. So in a way, this book is an explanation about why this untranslatable term and the entire current debate about who is perceived as a ‘part’ of Germany causes so much pain for those on the receiving end. Fourteen authors, among them Sharon Dodua Otoo, Max Czollek, Olga Grjasnowa, Margarete Stokowski, Reyhan Şahin (aka Lady Bitch Ray) and Simone Dede Ayivi, took up this task and brought their perspectives to paper in chapters named “visibility”, “work”, “trust”, “love”, “privileges”, “language”, and “sex” (among others).

Many of the stories resonate with Reni Eddo-Lodge’s and Afua Hirsch’s books. The othering and racism the authors suffered, their reactions to it, the way they changed after having kids (to name just a few). It’s painful to read, as it should be. The books also share a call for more solidarity and a call for action. Simone Dede Ayivi, for example, describes how important it was for her to experience that other people are fighting against racism, too, and she is not the only one.

As if the book wanted to prove that belonging works on a deeper level than looks and passports, when comparing the German writing to the British texts, I couldn’t help but notice how German the texts in Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum are. I tried to put my finger on it and I think it’s a specific way to express thoughts in an unnecessarily complicated way and to root as much as possible in theories. I know that a sound theoretical foundation can be quite helpful sometimes, but I fear that it doesn’t make the book very accessible. Maybe it doesn’t have to – maybe it’s even a playful hint at different exclusion mechanisms? – and I don’t expect texts about racism, othering and belonging to be a light read. But I fear this might make it harder for those who are not already thinking and reading about these topics to stick till the end. Not all of the texts are like this and I haven’t read them all, yet – it’s a reading in progress after all – but how the texts differ from those published in Britain (in particular the texts in the beginning) is something that struck me.

So far, my favourite text was written by Hengameh Yaghoobifarah, who is also one of the co-editors of the collection. Straight to the point and with a dry sense of humour. It made me curious to read more by the author. The text patiently explains the “white gaze”, body politics, and aspects of intersectionality to an audience that might not already be familiar with it, without being patronising or overly theoretical. And Sharon Dodua Otoo’s very personal text touched me: it’s a conversation with her 19-year-old son about how he was raised with the vocabulary to call out racist behaviour, but also about his struggles caused by this knowledge, institutionalised racism and he would have wanted (from his teachers in particular). Sharon Dodua Otoo then also reflects on how her parents have raised her growing up in London and this, again, had many similarities with Afua Hirsch’s accounts of her childhood.

I see the cover of this essay collection as a clear nod towards Reni Eddo-Lodge’s book. I’m just sorry to say that my bookshop person didn’t really get it and sold me the book as “Heimat ist Albtraum” *sigh* Doesn’t matter apparently: The book is already in its 4th edition. Congratulations!

#EureHeimatIstUnserAlbtraum ist keine 20 Tage draußen und geht schon in die 4. Auflage. ? Danke an alle, die mit uns träumen – und an alle, die unsere Träume zum Platzen bringen wollen, für die Bomben-PR. ?

— Prada Loth (@habibitus) March 12, 2019

Stop asking!

Reni Eddo-Lodge and Afua Hirsch and some authors in Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum talk about “The Question”, i.e. the “Where are you originally from” question they face so often, implying they could not possibly be British or German respectively. The journalist Ferda Ataman, who is an active member of “Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen” and who I had the great pleasure to meet at the Read Berlin festival with the group “Daughters and Sons of Gastarbeiters”, wrote a whole book about this obnoxious and imposing question: Hört auf zu fragen ICH BIN VON HIER! (S. Fischer, 2019)

I really enjoy her style and tone. She is rather direct and great at code switching. She somehow manages to talk about the serious problems of othering and racism with just the amount of humour that keeps readers going, but without making them too comfortable.

“Everything was fine when Fatma was cleaning toilets and Ali worked as a dustman. But when both want to be teachers – or even have an eye on a management position – all of a sudden they [disapproving Germans] feel like strangers in their own country. Now if Native Teutonics have issues with upward mobile immigrants and their descendants, this is not a justified concern; it is jealousy. Or, more academically: they want to keep the privilege they enjoy as an established group. In science this is also known as racism.”

(my translation)

Ferda Ataman calls out racist behaviour and the complicity of the media if they use words like Überfremdung and migration crisis without questioning it – and I love the PONS translation of “Überfremdung” and just have to share it here: “the irrational fear of being swamped by foreign influences is taking hold throughout the whole of Europe“.

Ferda Ataman denounces the calls for integration that really mean assimilation, the terrible Leitkultur waffle, the lie that you can do anything if you just work hard… She’s a woman on a mission! And at the end of each subsection she comes up with constructive suggestions how to replace these old concepts and behaviour patterns with better ones, e.g. how to change the concept of “integration” radically and widen the focus to families with children, unemployed and poor people, people in need of care etc., followed by respective measures and money for a sound and welcoming infrastructure (libraries included!). Ferda Ataman’s suggestion for a new and more inclusive way to think and talk about “Heimat” can also be found in the article she wrote for the antiracist Amadeu Antonio foundation (link to her article; in German).

The Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen (link to their website; German and English), a journalist association that Ferda Ataman chairs, aim to improve the German media landscape by fighting, writing and broadcasting for a more “balanced and nuanced media coverage on issues of diversity, migration and integration”. They want this to become “a matter of course” instead of an exception and they want to “foster a culture of recognition that values the potentials of a diverse society.” In this spirit, Hört auf zu fragen ICH BIN VON HIER! comes with a reading list of thirty-some (non-fiction) text written by “New Germans” (her words). Check it out!

Many more…

When I talked to my friend Wiebke Beushausen about this new category and the books I’m currently reading, she suggested including Desintegriert euch (Hanser, 2018) by Max Czollek to incorporate antisemitism to the spectrum. Max Czollek shows how absurd the unwritten but not less present requests to what a “good immigrant” needs to be like are – and he attacks the idea of a “one true Leitkultur” that is so often referred to when talking about integration in Germany.

And of course, one could add even more books that deal with similar topics and takes on othering and how to create a more convivial society. Many of the aspects brought up by Reni Eddo-Lodge and Afua Hirsch reminded me of the Nasty Women and The Good Immigrant collections. Fortunately, many books are currently published in this area. Unfortunately, they are still very necessary. So please feel free to send me suggestion via email or twitter – I’ll include them in the list below.

Reading list (to be continued):

- Reni Eddo-Lodge: Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. (Bloomsbury, 2017) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Afua Hirsch: Brit(ish). (Jonathan Cape, 2017) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Fatma Aydemir, Hengameh Yaghoobifarah (eds.): Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum. (ullstein, 2019) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Ferda Ataman: Ich bin von hier. Hört auf zu fragen! (S. Fischer, 2019) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Mariam Khan: It’s Not About the Burqa: Muslim Women on Faith, Feminism, Sexuality and Race. (Picador, 2019) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Nikesh Shukla (ed.): The Good Immigrant (Unbound, 201X) – now there’s also a The Good Immigrant USA edition, edited by Chimene Suleyman and Nikesh Shukla (Dialogue Books, 2019) (link to the publisher’s book site UK / US)

- Max Czollek: Desintegriert euch! (Hanser, 2018) (link to the publisher’s book site)

- Laura (eds.): Nasty Women (404ink, 2017) (link to the book’s contributors’ site)