(The quote in the title is from the poem “Tough” by Tony Walsh (aka Longfella), published in Common People: An Anthology of Working Class Writers, ed. by Kit de Waal (Unbound, 2019).)

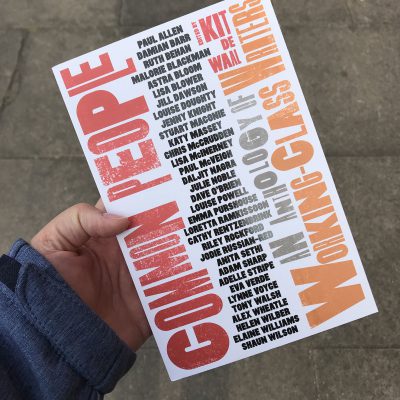

On International Workers Day 2019, the anthology Common People was launched (first in a pub, then at the Southbank Centre in London). It is a collection of short text written by authors who define themselves as working-class – 17 debut writers and 17 established ones. The anthology was edited by Kit de Waal and crowdfunded through Unbound.

“Written in celebration, not apology“ is a phrase that came up time and again – and it made me realise again how many stereotypical working-class characters and stories I had come across in books, on TV and on the news in general. Well, Common People is a welcome alternative to those; it’s truly a kaleidoscope of perspectives and stories – and indeed hard to sum up.

Cheers!

Kit de Waal speaking at the launch

But let me start with the launch! I have never been to a launch with such a welcoming atmosphere. When I entered the pub, I knew nobody in there – and half an hour later we were discussing everything from literature over beer to Brexit. I’ve never been to a launch with so many genuinely friendly people – and so few who felt the need to play ‘busy and important’ (in fact, I didn’t meet any that day).

When Tony Walsh (aka Longfella) recited his poem “Tough” (the first contribution in the book), everybody in the room joined in for the refrain. Here’s the first stanza:

They don’t like it when we make it despite all their ifs and cuts

They don’t like it when we take it as our rights to shake things up

They don’t like it when rough voices start demanding better choices

But it’s tough, we’ve had enough and we are coming

I still get goose bumps when I think about it. This evening at the pub and Southbank Centre showed me how good solidarity and celebrating each other can feel and that book launches can be much nicer than they often are.

- Southbank Centre, London

- Kit de Waal, Anita Sethi and Katy Massey talking about their texts and what it means to be working class in Britain today.

Celebration and Encouragement

I met loads of interesting people through the two launch events and the book. I experienced work on a construction site with Paul Allen, visited the friendly brothel next door with Katy Massey, took the tower block elevators with Loretta Ramkissoon and found sanctuary in literature with Eva Verde. The stories are not ‘epic’ tales, but rather glimpses, memories or episodes from the authors’ childhoods, recollections of food and daily routines, triumphs over parents, stories about breaking away from expectations. Anita Sethi, who also read at the Southbank Centre launch along with Katy Massey, wrote about how it felt as a kid to leave the city (Manchester) to go to the Lake District and how this journey had a transformative and long-lasting effect on her life – even though her place there was questioned.

Libraries come up time and again – as do cuts. And yes, some of the stories talk about death, violence, being ostracised, abuse and racism. But the stories are neither misery memoirs nor poverty porn and they are also not accounts of what the UK needs to do to fix inequality. The stories are ‘simply’ taking up space to tell a story from a particular perspective that often does not get this space, at least not in mainstream publishing. And they’re so much more nuanced than the working-class stories published from a middle-class gaze.

Libraries come up time and again – as do cuts. And yes, some of the stories talk about death, violence, being ostracised, abuse and racism. But the stories are neither misery memoirs nor poverty porn and they are also not accounts of what the UK needs to do to fix inequality. The stories are ‘simply’ taking up space to tell a story from a particular perspective that often does not get this space, at least not in mainstream publishing. And they’re so much more nuanced than the working-class stories published from a middle-class gaze.

Another aspect worth mentioning is that Common People did not only bring debut and established authors together, but Kit (and the literature development organisations involved) made sure that the texts also reflected the regional diversity of British working-class voices (something that does not seem to come naturally to many other publishing projects…).

I think there is some kind of connection between Lisa McInherney’s “Working Class: An Escape Manual” contribution in the beginning and Dave O’Brien’s last essay about “Class and Publishing: Who is Missing from the Numbers?” Lisa writes on a meta level about writing as a working-class author, how the literary field works and often succeeds in “keeping you in your box”. Dave’s text (as Gesa mentioned in a previous post (link)) asks who has the power to call the shots and gives us a glimpse of how middle-class publishing is – and why.

What I understand more and more about publishing is that it is not as creative as you’d expect from a ‘creative industry’. More often than not it seems to be intent on recreating past successes while at the same time obsessed with all things ‘new’ – but more along the lines of something they can make look new, while it’s not too different to rock the boat at the same time. Of course, there are exceptions, but there is also the mainstream.

The anthology gave working-class writers a platform to write from their perspective, managed to create a lot of buzz and attention around the book and, not least, encouraged people to think more nuancedly about working-class writers and stories. But Common People is more than the book alone. It’s a whole journey, a project designed to challenge and change publishing.

Common People – Programme, Report, Intervention

What might be less known than the actual book is the Common People project. It went on for a full year and accompanied the new or emerging writers who participated in the Common People anthology. Various events and activities run by the regional writing agencies – New Writing North, Writing West Midlands, Writing East Midlands, Spread the Word, New Writing South, National Centre for Writing and Literature Works – as well as a report written by Prof Katy Shaw at Northumbria University Newcastle with the aim to make it a sustainable project and role model rather than a one-off.

The project ran for 12 months and “aimed to create a strategic model of intervention to address the under-representation of working-class writers in publishing today.” The professional development programme included

- one-to-one mentoring with an established writer and support from the emerging writers’ regional writing development agency,

- two professional development days with opportunities to hear from publishers, agents, funders and the Society of Authors, and to build peer networks

- financial support e.g. for meetings with potential agents or publishers, PR activities and events

- free access to writer-development activities being run by the seven writer development agencies during this period

As Kit de Waal claims in her foreword: “This research report shows what targeted and funded creative industry interventions can do.” And, indeed, it reads like a success story: participants are now better connected among peers and in the industry, feel more confident and saw an improvement in their writing skills – and 60% now have literary agents or publishing contracts (source: Common People report). And Prof Shaw adds that “many mentors reflected that taking part in the programme […] also enhanced their own awareness of new talent and the development needs of emergent authors.”

As Kit de Waal claims in her foreword: “This research report shows what targeted and funded creative industry interventions can do.” And, indeed, it reads like a success story: participants are now better connected among peers and in the industry, feel more confident and saw an improvement in their writing skills – and 60% now have literary agents or publishing contracts (source: Common People report). And Prof Shaw adds that “many mentors reflected that taking part in the programme […] also enhanced their own awareness of new talent and the development needs of emergent authors.”

Prof Katy Shaw used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods for the Common People: Breaking the Class Ceiling in UK Publishing report (link) and asked the participating authors (the ‘new’ writers in the anthology) to reflect upon their experiences. In her report, she addresses the barriers for working-class creatives who want to be writers as well as interventions that have proven helpful. She concludes with recommendations about what writers can do, but also a call for publishers and agents to get out of their way (i.e. London) and broaden their horizons (she put it in much nicer words).

The recommendations are not surprising: more money for regional writing development agencies (who are best suited to identify and nurture new talent as well as create networks with the industry and among writers, but underfunded), decentralisation of the publishing industry (location, workforce, authors, audiences), searching for authors beyond London and being aware of the multiple barriers under-represented writers face – but apparently they need to be reiterated again and again!

The Common People Report is launched today. You can access it here: www.newwritingnorth.com/common-people

And I read in the announcements that they will also launch a new Common People podcast next week with contributions from leading writers and industry and academic experts – so keep an eye on their website as well as on the pages of the literature development organisations. There are so many exciting projects and interesting authors to discover there!

The Common People project can definitely serve as a good practice example for future projects – unfortunately, there are enough people and voices that are still marginalised.

Irish working-class writers – The 32

One follow-up project has already taken off! Paul McVeigh, who write “The Night of the Hunchback” in Common People, started a new crowdfunding campaign for Irish working-class writers. The 32: An Anthology of Irish Working-Class Voices will bring together 16 well-known writers from working class backgrounds with another 16 new and emerging writers from all over Ireland (both parts). Paul writes on the Unbound site: “Too often, working class writers find that the hurdles they have to leap are higher and harder to cross than for writers from more affluent backgrounds. The 32 will see writers who have made that leap reach back to give a helping hand to those coming up behind.”

The 32: An Anthology of Irish Working-Class Voices is already successfully funded, but if you want to, you can still contribute to it here: link to the crowdfunding page.

The (un)welcoming industry

But I don’t want to end on an all too happy note. There are still undeniably groups that are more visible in the literary field than others. I’ll go back to a report that Kit de Waal did for the BBC in 2017 to sum up a couple of the inclusion or diversity problems the industry has.

In her piece for the BBC (link to the recording), Kit de Waal talks to a range of writers, agents and publishers about what the barriers are for writers from working class backgrounds, including Tim Lott, Andrew McMillan, Gena-mour Barrett, CEO of Penguin Random House UK Tom Weldon, Julia Bell, Julia Kingsford, Ben Gwalchmai, Nathan Connolly and Stephen Morrison-Burke (Birmingham poet laureate and the first recipient of the Kit de Waal scholarship).

Access is a recurring theme – access to the often monocultural and London centric networks, access to a profession with very unstable income expectations. Nathan Connolly, director of the indie publisher Dead Ink Books, already anticipated what Katy Shaw’s Common People report states, too: “I think we need to start looking at moving not just publishing, but other creative industries, outside of London.” When asked what the industry could do to be more welcoming, Nathan says: “First I think they need to publish more working-class writers. There are a lot of things which could be done but I don’t think there is anything quite as powerful as being able to see someone from your own background, seeing an element of yourself reflected in that.” And along with this would hopefully also come more nuanced representations of working-class characters.

Kit de Waal concludes: “There are writers and readers in the working- and underclasses, ready to see their lives depicted in literature; stories that speak of their concerns and their lifestyles, written with authenticity and humour – from beyond the metropolitan elite. There are stories already written that deserve to be read; and new stories that will remain lost or untold until something changes.”

Kit’s audio production for the BBC is from 2017 (when Know Your Place was published). Has the field become less monocultural in its workforce and stories? I’m sceptical. And I believe that publishers still have a particular core audience in mind when they acquire and package books – and I don’t believe it’s very diverse in terms of class (or anything). Are we at a point, yet, where working-class writers are ‘allowed’ to write about anything they want? I suspect that publishers still look for working-class writers who produce a certain narrative that publishers think appeals to their imagined white middle-class readership. I believe this is a huge disservice to all of us – and I have a feeling that I will get back to this point in some future posts…

Kit de Waal and the Common People authors managed to do things differently. The stories were “written in celebration, not apology“, and they’re neither uncritical or sugar-coating nor providing the usual misery memoirs either. Do read the stories, if you haven’t done so already, and follow the authors – they’re really interesting people, activists, and writers!

Links

- Common People: An Anthology of Working Class Writers, ed. by Kit de Waal (Unbound, 2019): www.unbound.com/books/common-people/

- The 32: An Anthology of Working Class Voices , ed. by Paul McVeigh (Unbound, 2020), ongoing crowdfunding: www.unbound.com/books/32/

- Katy Shaw, Common People: Breaking the Class Ceiling in UK Publishing, www.newwritingnorth.com/common-people

- Kit de Waal on BBC Radio4: “Where are all the working-class writers?” by Kit de Waal on BBC Radio 4, 23 Nov 2017, www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b09fzmjt

- Know Your Place: Essays on the Working Class by the Working Class, ed. By Nathan Connolly (Dead Ink Books, 2017) www.deadinkbooks.com/product/know-your-place/

Literature Development Organisations

- Spread the Word: www.spreadtheword.org.uk

- Writing West Midlands: www.writingwestmidlands.org

- Writing East Midlands: www.writingeastmidlands.co.uk

- New Writing North: www.newwritingnorth.com

- New Writing South: www.newwritingsouth.com

- National Centre for Writing: www.nationalcentreforwriting.org.uk

- Literature Works: www.literatureworks.org.uk